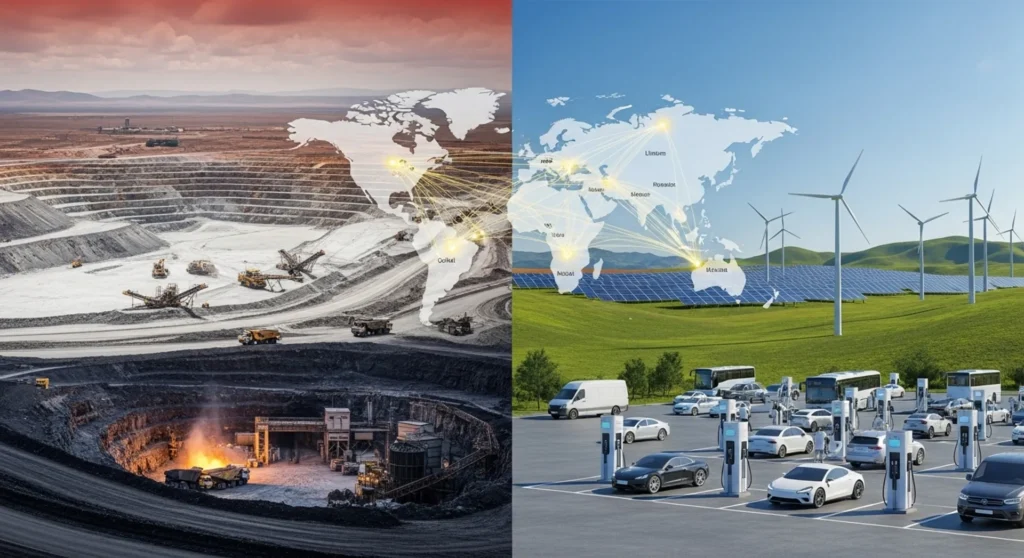

The global energy transition is fundamentally reshaping international relations, but not in the way most people expect. While renewable energy promises to reduce dependence on fossil fuels, it has created an entirely new form of resource competition centered on critical minerals. Nations worldwide are now scrambling to secure access to lithium, cobalt, copper, nickel, and rare earth elements — the building blocks of our clean energy future.

The Rising Importance of Critical Minerals in Energy Transitions

Critical minerals have emerged as the silent architects of the 21st-century energy landscape. According to the International Energy Agency’s 2025 Critical Minerals Outlook, demand for these essential resources is projected to double by 2030, with some minerals like lithium expected to see demand increase four to six times over current levels. This exponential growth is driven by the rapid deployment of electric vehicles, wind turbines, solar panels, and battery storage systems.

The geopolitical implications are profound. Unlike oil and gas, which are concentrated in specific regions, critical minerals present a different challenge. While extraction sites are geographically diverse, the processing and refining capacity remains dangerously concentrated. China currently controls between 50% and 90% of global refining capacity for most critical minerals, creating a strategic vulnerability that has alarmed policymakers from Washington to Brussels.

Supply Chain Vulnerabilities and Strategic Dependencies

The concentration of critical mineral supply chains represents one of the most significant diplomatic challenges of our time. The Democratic Republic of Congo produces approximately 70% of the world’s cobalt, Chile dominates lithium extraction, and Indonesia has become the primary source of nickel. This geographic concentration, combined with China’s refining dominance, creates multiple chokepoints that could be exploited during geopolitical tensions.

The China Factor in Critical Minerals Processing

China’s strategic positioning in the critical minerals value chain is no accident. Over the past two decades, Beijing has systematically invested in mining operations, processing facilities, and refining capacity worldwide. Chinese companies have acquired stakes in lithium projects in Australia, cobalt mines in the Congo, and rare earth element deposits across Africa and Latin America. This vertical integration gives China unprecedented influence over the supply chains that underpin the global energy transition.

The World Economic Forum warns that this concentration poses significant risks to supply chain resilience, particularly as demand intensifies. For countries pursuing ambitious climate goals, dependence on a single supplier for critical minerals creates a strategic vulnerability comparable to — or potentially exceeding — previous dependencies on Middle Eastern oil.

Emerging Producer Nations and New Diplomatic Relationships

The critical minerals economy is creating opportunities for nations that were previously peripheral to global energy diplomacy. Countries like Chile, Australia, Namibia, and Morocco are positioning themselves as essential partners in the energy transition. This shift is fostering new bilateral relationships and diplomatic alignments that differ markedly from traditional energy partnerships.

Understanding these evolving dynamics requires recognizing how energy security frameworks are adapting to new realities. The traditional focus on supply reliability is expanding to encompass the entire critical minerals value chain, from extraction to processing to end-use applications.

Diplomatic Strategies for Critical Minerals Security

Governments worldwide are deploying various diplomatic tools to secure critical mineral supplies and diversify supply chains. These strategies range from bilateral partnerships to multilateral frameworks, each with distinct advantages and challenges.

Bilateral Partnerships and Strategic Agreements

The United States, European Union, Japan, and other major economies are negotiating bilateral agreements with mineral-rich nations. These partnerships typically combine trade arrangements with technology transfer, infrastructure investment, and development assistance. The goal is to create mutually beneficial relationships that reduce dependence on Chinese processing while supporting economic development in producer countries.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development emphasizes that these partnerships must prioritize fair benefit-sharing and local value addition to ensure developing countries can fully capitalize on their mineral wealth rather than remaining trapped in commodity dependency.

Multilateral Initiatives and Governance Frameworks

Multilateral approaches are also gaining traction. The Minerals Security Partnership, launched in 2022, brings together major economies to coordinate investments in critical mineral supply chains. The initiative aims to support projects that meet high environmental, social, and governance standards while diversifying global supply sources.

Similarly, the UN Secretary-General’s Panel on Critical Energy Transition Minerals is developing voluntary global principles to ensure that mineral extraction and processing benefit all countries and communities. These frameworks recognize that effective energy diplomacy requires balancing strategic interests with sustainability and equity considerations.

Environmental and Social Dimensions of Mineral Extraction

The race to secure critical minerals cannot ignore the environmental and social costs of extraction and processing. Open-pit mining, the standard method for extracting lithium, cobalt, and nickel, is energy-intensive and causes significant environmental degradation. Groundwater contamination, habitat destruction, and greenhouse gas emissions accompany many mining operations.

Human rights concerns compound environmental challenges. Artisanal cobalt mining in the Democratic Republic of Congo has been linked to child labor and dangerous working conditions. These ethical dimensions create diplomatic complications, as importing nations face pressure to ensure their supply chains meet acceptable standards.

The Role of Recycling and Circular Economy Approaches

Recycling offers a promising pathway to reduce pressure on primary extraction. If properly scaled, recycled sources could meet up to 40% of future demand for metals like cobalt and copper, and 25% for lithium and nickel. Investing in recycling infrastructure and circular economy models represents both a technical solution and a diplomatic opportunity, potentially reducing geopolitical tensions over primary resources.

The integration of advanced technologies into mineral supply chains connects directly to broader trends in digital transformation and smart energy systems, where innovation can help optimize resource use and reduce waste.

Policy Recommendations for Energy Diplomacy Practitioners

Addressing critical minerals geopolitics requires coordinated action across multiple dimensions. First, countries must invest in domestic processing capacity to reduce dependence on single suppliers. This requires not only capital investment but also workforce development and environmental safeguards.

Second, diplomatic engagement should prioritize partnerships with emerging producer nations based on mutual benefit and sustainable development principles. Resource-rich developing countries need technology transfer, infrastructure support, and market access to move beyond raw material exports and capture more value from their mineral wealth.

Third, international cooperation on standards and governance is essential. Harmonized certification schemes for responsibly sourced minerals can help ensure that the energy transition doesn’t come at unacceptable environmental or social costs. The UN Environment Programme is working with stakeholders to develop frameworks that balance supply security with sustainability imperatives.

The Path Forward: Balancing Competition and Cooperation

Critical minerals geopolitics presents both challenges and opportunities for international relations. While competition for resources could exacerbate tensions, it also creates incentives for cooperation. No single country can achieve energy transition goals in isolation; interdependence is inevitable.

The question is whether this interdependence will be characterized by zero-sum competition or by collaborative frameworks that distribute benefits equitably. Energy diplomacy has a crucial role to play in shaping this outcome. By fostering transparent markets, supporting sustainable extraction, and building resilient supply chains, diplomatic practitioners can help ensure that the energy transition strengthens rather than undermines global stability.

As nations navigate this complex landscape, the principles of collaboration, innovation, equity, and sustainability — central to effective energy diplomacy — will prove more important than ever. The critical minerals challenge is ultimately not just about securing resources; it’s about building a more sustainable, equitable, and secure energy future for all.